Who am I?

Who am I?

Don’t worry, this article isn’t going to go all jingoistic or introspective. It tackles the knotty issue Indian returnees face accessing numerous online and offline services – proving they are, who they claim. Authentication of IDs hinges on a handful of critical documents – PAN cards to prove their (financial) existence, Aadhaar Card to prove their address, a driving licence and an Indian mobile number which provides traders an entry point to unending marketing texts. (I am not joking; some cash registers need a valid phone mobile number to complete a sale.)

India has fused its obsession with tech with its love of needless bureaucratic complexity to make life with these documents less predatory, and life without like an episode of Black Mirror.

So, what are these documents, why were they developed, and how easy are they to get hold of. And what happens to those on the wrong side of the ID face-off?

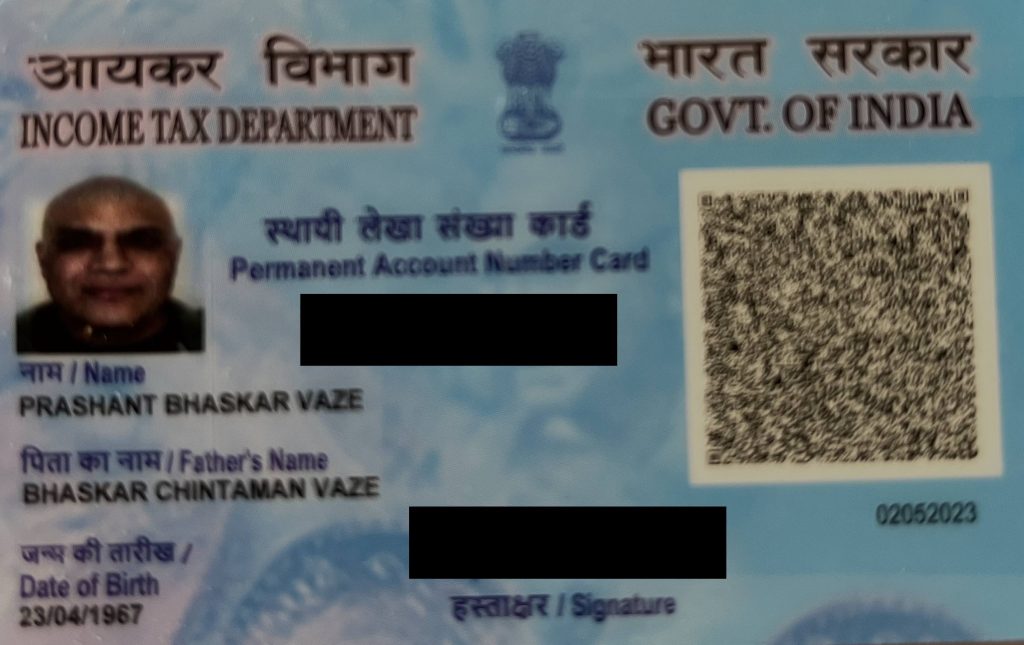

The Permanent Account Number (PAN) is a ten-digit alphanumeric number, issued by two private companies – NSDL for online applicants, and UTI-TSL for paper-based applications – on behalf of the Income Tax Department. The UK equivalent is a National Insurance Number. (An interesting aside is that the code’s fourth character identifies the class of the applicant. ‘H’ signifies Hindu Undivided Family, and ‘J’ an Artificial Juridical Person, gratifying ChatGPT but leaving fractious, non-Hindu families beleaguered). You need a PAN to open a bank or savings account, purchase a car, insurance, jewellery, or property, apply for a phone number, and pay more than Rs 50,000 (£500) at a hotel or restaurant. The rationale for demanding PAN numbers is that India has a big problem with black money, and making buyers disclose PAN numbers cracks-down on crooks’ efforts to clean their loot.

The Permanent Account Number (PAN) is a ten-digit alphanumeric number, issued by two private companies – NSDL for online applicants, and UTI-TSL for paper-based applications – on behalf of the Income Tax Department. The UK equivalent is a National Insurance Number. (An interesting aside is that the code’s fourth character identifies the class of the applicant. ‘H’ signifies Hindu Undivided Family, and ‘J’ an Artificial Juridical Person, gratifying ChatGPT but leaving fractious, non-Hindu families beleaguered). You need a PAN to open a bank or savings account, purchase a car, insurance, jewellery, or property, apply for a phone number, and pay more than Rs 50,000 (£500) at a hotel or restaurant. The rationale for demanding PAN numbers is that India has a big problem with black money, and making buyers disclose PAN numbers cracks-down on crooks’ efforts to clean their loot.

On paper, all that’s needed to acquire a PAN card are two photos, proof of address (PoA) and proof of identity (PoI). In February, I first tried the online method but got stuck finding an acceptable PoA. I went to the UTI-TSL office to see if my bank account statement or tenancy agreement worked. The scrum of people outside the office would have terrified the All Blacks. I couldn’t get close enough to the counter even to pick up an application form. Reluctantly, I did what I had vowed not to do – got an agent. She deemed my bank account statement and tenancy agreement were useless. Only government-issued documents could be used, or affidavits by elected politicians. The agent instructed me to use a relative’s address as proof of an Indian address. My application got rejected twice before the resolution of my relative’s Aadhaar card satisfied the NSDL. After ten weeks, I was a proud owner of a PAN card enabling me to pay income tax.

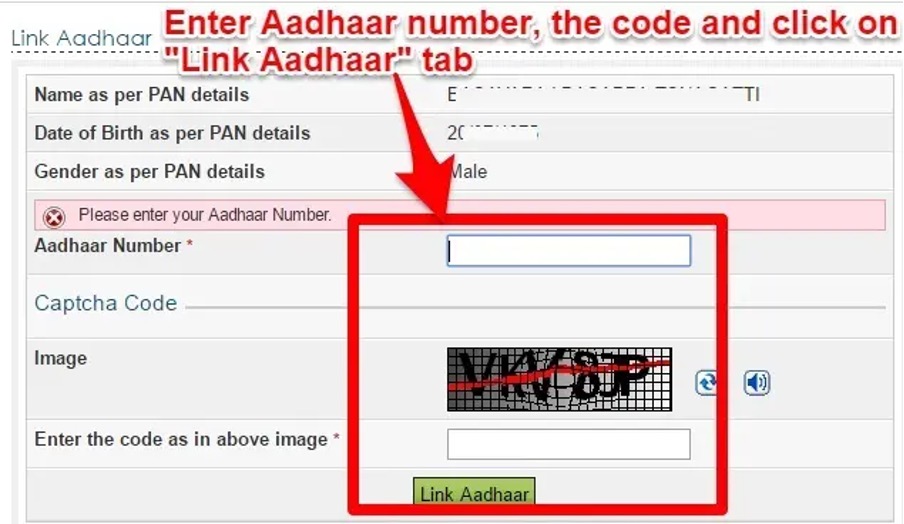

The Aadhaar card (a twelve-digit number and small booklet) started in 2009 as a voluntary scheme of rationalising government citizen databases. UIDAI administers it. Enrolment has been a wild success, and 99.9% of Indians have a card. Name, address, gender and date of birth are included alongside photos, fingerprints and iris scan biometric identifiers. Routine use of the card has reduced parasitic intermediaries from inserting themselves between Indian citizens and their entitlements to welfare benefits, work schemes like MG-REGA, food rations, and subsidised fuel (LPG). The government is linking Aadhaar to PAN cards and India’s electronic payment systems allowing millions of unbanked Indians with a secure payment system. It was used 2. 31 billion times in March 2023 alone. In the UK, HMRC and DWP maintain separate and unlinked databases of taxpayers and claimants.

Increasingly the private sector demands an Aadhaar card, with its reliable biometric identifiers, to prove ID. Employers are said to use the card to track employee workplace attendance.

So how do I get one? The success of the enrolment programme meant that most Aadhaar centres were closed just before we arrived, and the rules governing new applications were quietly removed. I travelled twenty miles to the nearest remaining centre in Goa and was told (at 11 am) that the officer had gone for lunch, and to come back after lunch. I bullied the receptionist into showing me the latest staff circular, which essentially said to come back in March, maybe April when the new rules would be revealed. It turns out, foreigners can apply for an Aadhaar card once they have lived in India for 182 days. So now I wait.

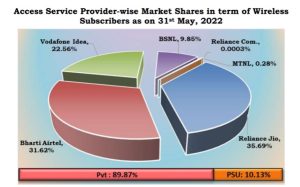

Indian mobile phone numbers are another must-have. All sorts of online and offline transactions require you to submit one-time passwords (OTPs) to complete the sale. Officials use texts to communicate time-critical information. For my sleeper train ticket to Delhi, carriage and seat number were delivered via text. So too updates about my PAN application. No wonder India has 1.2 billion active mobile phone numbers, a higher penetration rate than Europe. The competition between Indian mobile providers is ferocious, with four major suppliers. Two were set up by the warring Ambani brothers Airtel (Anil till bankruptcy in 2019) and Jio (Mukesh), Vodafone-Idea (now divested from Vodafone UK) and one other no-ones heard of.

Getting an Indian SIM card is less straightforward than in the UK, but not hard. You quickly hit the familiar chicken-and-egg issue of supplying an Indian address and PAN card which many foreigners won’t possess. Luckily the telephone service providers were happy with my wife’s PAN card and property documents, and I got in on her shirttail. This paved the way for localised (and vastly cheaper) versions of Spotify, Apple Store and Google Pay.

Getting an Indian SIM card is less straightforward than in the UK, but not hard. You quickly hit the familiar chicken-and-egg issue of supplying an Indian address and PAN card which many foreigners won’t possess. Luckily the telephone service providers were happy with my wife’s PAN card and property documents, and I got in on her shirttail. This paved the way for localised (and vastly cheaper) versions of Spotify, Apple Store and Google Pay.

I can legally drive in India for a year using an international license. I hope this will give me enough time to obtain an Indian license. This should be issued to holders of a valid international license. The online application took five-minutes and I got a reassuring email saying I should “visit the concerned office with required forms and documents along with this receipt”. Again an acceptable Proof of (Indian) Address will be needed, which sometimes gums up the process. An American neighbour who moved to India a year ago needed an ‘agent’, assisted by a Rs 14,000 under-the-counter payment, which overnight sorted out the mysterious obstacle holding up his nonconforming address. Such under-the-table payments to agents are all too often needed to access public services and licenses. According to a 2007 academic article by IFC staffers, which included a fascinating behavioural experiment, the likelihood of passing a driving test was unrelated to the ability to drive. The arbitrary failing of test candidates was simply to steer them towards ‘agents’. Sadly, for the bureaucrats, much of the bribe went to the agent rather than the bent bureaucrats.

Life without valid ID documents is possible, but awkward. At a car showroom, I asked what I needed to buy and register a car: PAN number to pay the road tax…fair enough, but the Aadhaar card was needed to prove my ID. I have plenty of other identification documents I protested. The salesman said he’d give his permitting contact in the RTO (regional transport office of which Goa has ten employing 350 staff!) a call. He got back a few days later, saying a small fee could be paid to smooth the way for such an irregular application. He was being blunt, that’s how things work here.

The diktats about better regulation and plain English which swept over UK and the EU public sectors haven’t made it to India yet. It carries on with its pre-Independence mindset. These processes are a throwback to the Raj, when the bureaucracy was a weapon of subjugation and rent extraction, rather than a service provider. IT permits India’s bureaucracy to become more streamlined, but it faces resistance from the vast army of people employed (and sometimes profiting) from the old license Raj. David Graeber would have developed a more textured and nuanced Bullshit Jobs thesis had he done his fieldwork in India. This sort of makework, a term commonly used in India, but I’d not heard before, is frustrating for us and often for many public-minded officials too.

And therein lies the conundrum for India, the obstacle to better public services isn’t technology but what to do with the army of bureaucrats and agents that evolved before the streamlining provided by the technology. And this is before ChatGPT sends another shock wave of redundancy to many of the pen-pushing rigmaroles of obtaining ID documents.

Prashant, A perfect dissection of the pen pushing bureaucracy! Love it. Please do one on using international credit or debit cards in India.