I last lived in India in 1977 as a schoolboy in Nagpur, famous for oranges and not much else. With a few months left before their ‘indefinite leave to remain’ visas lapsed; my parents called time on their two-year sojourn in India. Sure, I’ve since visited for work or family occasions, but India was just a backdrop for something else. Usually, I was reeling with jetlag, amidst a crush of half-remembered relatives at a wedding, or too overdosed on sight-seeing to pay attention to the changes that had occurred while I was gone. In any case, I wasn’t living in India I was breezing through its manicured hotels or couch surfing in relatives’ spare rooms.

The India I experienced half a lifetime ago was through ten-year-old eyes. I noticed beggars clustered around the temples my grandmother made me go to. Many of whom missed limbs, as India was home to around five million lepers. I remembered health-and-safety concern devoid Diwali fireworks in our backyard when my cousins and uncles packed kilotons of rockets under a steel bucket to despatch it into orbit. I loved holiday fairs with gaudy lights and charcoal flames, stalls selling peanuts boiled in brine, and Ferris wheels powered by steam-aged engines. My brother and I would travel back and forth to school in a cycle rickshaw and play in streets where cows walked freely, and cars were few.

Since moving here in February, I have seen no lepers, in fact, no beggars at all, though downtown Mumbai and Goa might only partially represent India. India’s efforts at space exploration have come on since my family’s pioneering efforts; its space agency has had success with its reusable launch vehicle programme, reducing the costs of deploying satellites. Maybe one day rivalling SpaceX. Cycle rickshaws have been replaced by CNG-fuelled three-wheeler autos or taxis. An ambitious but painfully slow build-out of Metros is being implemented in Mumbai and Nagpur. To date, Mumbai’s consists of three partial lines, which will one day rival those in Chinese cities. A couple of weekends ago, we took a forty-minute trip from Andheri to the Sanjay Gandhi National Park to see the 10th-century Buddhist Kanheri caves.

Since moving here in February, I have seen no lepers, in fact, no beggars at all, though downtown Mumbai and Goa might only partially represent India. India’s efforts at space exploration have come on since my family’s pioneering efforts; its space agency has had success with its reusable launch vehicle programme, reducing the costs of deploying satellites. Maybe one day rivalling SpaceX. Cycle rickshaws have been replaced by CNG-fuelled three-wheeler autos or taxis. An ambitious but painfully slow build-out of Metros is being implemented in Mumbai and Nagpur. To date, Mumbai’s consists of three partial lines, which will one day rival those in Chinese cities. A couple of weekends ago, we took a forty-minute trip from Andheri to the Sanjay Gandhi National Park to see the 10th-century Buddhist Kanheri caves.

The biggest change I see is that my Indian family has died or migrated. Few people are left in Nagpur. Many of my cousins have joined their parents and flowed into the huge Indian diaspora looking for better-paid jobs in Dubai, US, Australia, and Canada.

I’ve met many people who spent a few years overseas returning after a foreign degree and a few years of professional life in tech or Wall Street. Those that come back find the country’s plentiful domestic staff and cheap cost of living eclipse the obvious disadvantages. I write this having just chased the Devonian-era-sized cockroach across our spotless flat and spent a fitful night praying the sporadic power cuts would not deprive me of AC-induced sleep.

We’ve had to buy lots of things quickly. India is cheap, except for imports. Our broadband costs ₹799/month (£8/month), our 4G mobile monthly charge is around ₹500/mn, a pizza at our nearest 5-star hotel ₹900. Quality is comparable, if not better than UK. Streaming companies like Netflix, Amazon Prime and Spotify charge Indian customers hardly a tenth of UK prices. But to subscribe you need an Indian phone number, bank account perhaps IP location to prevent foreign free loaders. This implicit subsidy to the middle-class Indians (some £300 per person) dwarfs aid flows to the country!

India’s best-selling car, the Maruti Suzuki Baleno, costs ₹800,000 and has decent AC, sound system, sat-nav and rearview cameras. India used to be the last place in the world still making the Oxford Morris (twenty years after production ceased in UK), by contrast the 2015 iteration of the Baleno was launched in India a year ahead of its launch in the UK. Maruti-Suzuki now sells around two million cars annually, comprising two-thirds of its parent Suzuki’s global production. India has become a net exporter of cars, with a trade surplus in vehicles of $5.2bn.

India’s best-selling car, the Maruti Suzuki Baleno, costs ₹800,000 and has decent AC, sound system, sat-nav and rearview cameras. India used to be the last place in the world still making the Oxford Morris (twenty years after production ceased in UK), by contrast the 2015 iteration of the Baleno was launched in India a year ahead of its launch in the UK. Maruti-Suzuki now sells around two million cars annually, comprising two-thirds of its parent Suzuki’s global production. India has become a net exporter of cars, with a trade surplus in vehicles of $5.2bn.

The grown-up me is aware of many other changes in India over the last forty years. The Indian exchange rate dropped from 15₹/£ to around 100₹/£. The population has doubled from 650 million to 1.3 billion. GDP per head in purchasing power parity and constant 2017 USD has increased from $1,800/capita in 1990 to $6,600 in 2021. Over the same period, the global average increased by 70 per cent to $17,000. India’s cheapness is crucial; if you don’t adjust for the purchasing power parity, today’s per capita GDP is just $2000 / capita. The low prices for non-tradable goods like mobile phone tariffs and services like bus fares make life in India tolerable for Indians.

The steady fall in the exchange rate is puzzling. Much of it occurred between 1990 and 2000 and after 2007 and is despite India now being a significant exporter of services, manufacturing and even some food items. I’ll cover this in a future blog.

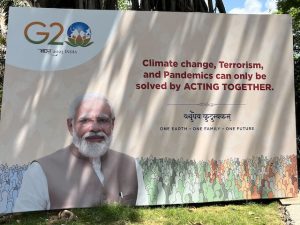

The other thing the grown-up me notices is the G20 summit. It’s hard to ignore. Omnipresent billboards declare One Earth, One Family, One Future, and the Prime Minister’s big brotherly face looks down on you constantly. Unlike the UK, India does not have much of a seat at the big boy’s table. Despite being the world’s fifth largest economy, it’s not a member of the G7, the UN’s security council, OECD, the EU, NATO, or any other place the big economies talk. Chairing the G20 is a big deal for the political classes. When I left India in 1977, the country was almost a pariah. Indira Gandhi had declared an Emergency, suspended the constitution, imprisoned political rivals, and postponed the general election. In September, Narendra Modi will welcome Biden, Xi Jinping, and the other heads of state. Goa is in a state of continuous reconstruction, awash with ‘Smart city’ and G20 funds to impress officials and second division ministers attending the eight meetings scheduled for the state.

The other thing the grown-up me notices is the G20 summit. It’s hard to ignore. Omnipresent billboards declare One Earth, One Family, One Future, and the Prime Minister’s big brotherly face looks down on you constantly. Unlike the UK, India does not have much of a seat at the big boy’s table. Despite being the world’s fifth largest economy, it’s not a member of the G7, the UN’s security council, OECD, the EU, NATO, or any other place the big economies talk. Chairing the G20 is a big deal for the political classes. When I left India in 1977, the country was almost a pariah. Indira Gandhi had declared an Emergency, suspended the constitution, imprisoned political rivals, and postponed the general election. In September, Narendra Modi will welcome Biden, Xi Jinping, and the other heads of state. Goa is in a state of continuous reconstruction, awash with ‘Smart city’ and G20 funds to impress officials and second division ministers attending the eight meetings scheduled for the state.

Many have asked why Maya and I upped sticks and relocated to India. India is changing fast, and we wanted to be here to watch, and help make its development more sustainable. We come armed with our OCI card, allowing us to work, and some savings. Goa is also an incredibly beautiful place to live and write. More on that in the next post.