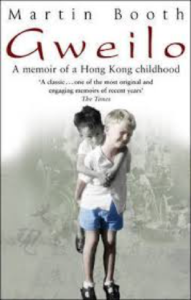

Just finished reading Martin Booth’s autobiographic book, the third of the Gweilo canon I’ve read these past few months. The three books couldn’t be more different. John Lanchester’s novel Fragrant Harbour covers the period between the end of the first world war and the turn of this century. He skilfully weaves three narrators and three narratives into an intergenerational saga. James Clavell’s Taipan is a swashbuckling story of an early Victorian privateer who outwits mandarins, pirates and business rivals to found an enduring business dynasty that loosely based on the Jardine story. Gweilo is set in the two-year stretch of time between 1952 and 1954 as seen through the eyes of the 8 to 10 year-old Booth. Booth’s father is a low ranking civil servant and his mother a vivacious and wise homemaker.

Just finished reading Martin Booth’s autobiographic book, the third of the Gweilo canon I’ve read these past few months. The three books couldn’t be more different. John Lanchester’s novel Fragrant Harbour covers the period between the end of the first world war and the turn of this century. He skilfully weaves three narrators and three narratives into an intergenerational saga. James Clavell’s Taipan is a swashbuckling story of an early Victorian privateer who outwits mandarins, pirates and business rivals to found an enduring business dynasty that loosely based on the Jardine story. Gweilo is set in the two-year stretch of time between 1952 and 1954 as seen through the eyes of the 8 to 10 year-old Booth. Booth’s father is a low ranking civil servant and his mother a vivacious and wise homemaker.

Reading it you realise a place is not so much geographic location as a period of time and a human perspective. So while you can spot familiar place-names which only another local might know – Old Peak Road, Mount Austin, Sham Shui Po – you also realise you’re reading about an entirely alien country. The Hong Kong being described in this book still has opium dens and people spitting in the street. The excellent public transport system is still in its gestation. Sha Tin and Tai Po are sleepy fishing villages accessed by single track roads already fully utilised by unswerving farmers herding their geese and cows. Nowadays both New Towns are settlements with quarter of a million residents each reached by MTR from Kowloon in 20 minutes. The Hong Kong people are colourful refugees fleeing the Mao’s communists’ predation of Chinese petite bourgeoisie. There is a hilarious description of a well-meaning relative who sends the family food and toiletries from a post-war rationed UK unbelieving of their pampered and sumptuously catered expat lifestyles.

Booth regards every fettering of his right-to-roam as a challenge. On being told he should not enter the notorious and lawless Kowloon Walled City: “To utter such a dictum to a street-wise eight-year old was tantamount to buying him an entrance ticket.” KWC has since been reformatted as a bucolic park and his description of the kindly triads, and brothels seems unimaginable . Surely even the most casual reader must see the contrast between Booth’s colourful childhood and the shopping mall-grade 8 viola lessons-Dr Spock maths crammer class existence that passes for childhood in Hong Kong these days.

The other striking feature of the book is the Oedipal complexity of his relationship with his inadequate, bullying and ultimately hated father. It’s an honest and often uncomfortable account of how a bad parent slips off their filial pedestals in their child’s eyes.

The book ends with the family boarding the boat back to England. There is a tantalising hint of a second book in which Booth and his mother return to HK sans father, but sadly the author dies soon after Gweilo is published so the next chapter remains untold. Curiously, I too spent the two years of my childhood between ages of 8 and 10 away from the UK, in India, when my parents tried to make a go of it back in the “mother country”. I only wish my recollections were as vivid and my days in India as eventful as Booth’s.