Image: P. Vaze, Salvadore de Mundo, Goa

The Indian Meteorological Department (IMD) declared a close on the Goa monsoon on 23 October, just nine days later than its long-range forecast’s predicted date. The start of the monsoon was similarly only five days later than predicted, and the volume of rain was just 6 per cent off.

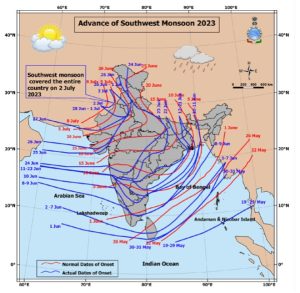

Figure 1: 2023 Southwest Monsoon’s arrival

I am used to dark tales about climate change making weather more volatile and India’s rural economy being crushed. Indeed, I am currently co-penning a report on the physical impacts of climate change on India, to inspire banks to up their game on climate-aware lending.

This Blog isn’t about physical climate change and how the world is going to hell in a rickshaw. This month’s focus is my surprise at IMD’s well-founded conceit about its divination powers. Nothing in India is ever on time or as per spec; how does IMD get to swagger about its forecasting prowess?

In Alexander Frater’s meandering 1990 travelogue Chasing the Monsoon, the rains arrive in Goa on 5 June, just a few days ahead of this year’s 10 June. Despite three decades of greenhouse gas emissions, there’s been hardly any change. (The book predicts that India’s population will grow to 1.2 billion by 2050 – a grotesque underestimate of our population growth rate).

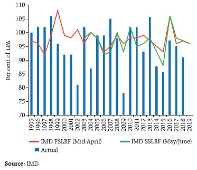

India takes the business of forecasting the southwest monsoon seriously. In 2018, IMD bought the Pratyushand Mihir supercomputers, reputedly India’s most powerful computers, to improve its Mid-April (First Stage Long-Range Forecast – FSLRF) and May/June (Second Stage Long-Range Forecast – SSLRF) forecasts. Only the US, UK and Japan Met Offices have comparable facilities. Such is the economic import of IMD’s forecasts, the RBI reviewed the models’ performance.

The IMD’s record on long-range monsoon forecasting has been patchy. It failed to predict the droughts of 2002 and 2009, and in an evaluation conducted in 2019, RBI found no correlation between the IMD forecast of the volume and the actual rain.

The IMD’s record on long-range monsoon forecasting has been patchy. It failed to predict the droughts of 2002 and 2009, and in an evaluation conducted in 2019, RBI found no correlation between the IMD forecast of the volume and the actual rain.

RBI also compared IMD’s forecasts with outputs from other global long-term weather models, which forecast the globally significant El Nino and La Nina phenomena. Back then, USA’s NOAA and Australia’s BOM offered better predictions of extreme monsoon years than India’s own models. I could not find any published evaluations of IMD’s performance since the purchase of its supercomputers.

Monsoon plays a big part in India’s annual prospects. Former President Pranab Mukherjee quipped the monsoon is India’s true finance minister. Around three-quarters of India’s annual rainfall arrives between June and September. Around 70 per cent of Indians live in villages many of them directly or indirectly depend for a living on rainfed agriculture.

View from my back window across the year

The volume of water that falls is awesome Deluge in Aldeia. Goa receives an average rainfall of 2900mm a year, five times London’s annual precipitation, and mostly mainly during monsoon. The pounding water cracks our estate’s laterite paving steps, craters the roads made from adulterated asphalt, and transforms the arid brown and ochre landscape to viridescence. Goa’s already substantial population of snakes, insects and birds go on a breeding frenzy. This year, we have to be on our guard for mosquitoes as they’re carrying virulent strain of dengue.

Figure 3: Paddy fields in Salcete ‘breadbasket of Goa’

Driving round Goa, it’s still possible to see why predicting the timing of the monsoon is so critical. Soon after the rains arrive, the ancient sluices are opened flooding the reclaimed Khazan land and month-old rice is swiftly transplanted from the nursey fields to the newly flooded paddy fields. Before the flood, the ridges and water channels have to be repaired and the fields manured to ensure the rice is ready to be harvested in September. Sadly, the manicured fields seen in Figure 3 are increasingly rare sight as farmers age and their children are drawn to better-paid urban jobs. The peculiarities of Portuguese law carving land into tiny parcels of subdivided land no longer provide income sufficient to justify cultivation.

To end, even if the supercomputers are unable to improve their long-term forecasts of monsoon, we can always rely on local clairvoyants like the weather babu.

.