On 15 March, the government introduced a policy to stimulate electric vehicle (EVs) manufacture in India. Government’s strategy for decarbonising transport leans heavily on its EV ambitions. The plan is by 2030, for 30% of new car, 70% of goods vehicles and 80% of scooters and rickshaws sales, to be EV. In tandem electricity will need to fully decarbonise over the next few decades.

The aspiration is for these vehicles to be domestically produced. Imports of EVs, like other road vehicles, are subject to India’s ferocious import duty regime. New vehicles with an import sticker price of more than $40,000 pay 100% import duty, those less than $40k pay 70% duty. Tesla has sought to negotiate a waiver for imports of its vehicles and promised to invest in a vehicle manufacture pant for local production.

To the government’s credit, it ignored Tesla’s entreaties for special treatment and last week’s announcement allows all foreign car manufacturer to import up to 8000 vehicles a year with a reduced 15% tariff, but in exchange they have to invest more than $500m in an Indian facility inside of 3 years and source half the components by value domestically within five years. In essence, a foreign car manufacturer gets to import 40,000 EVs at low tariffs over five-year netting around half a billion in profits (assuming $12,500 per vehicle) but in exchange has to invest those profits in creating a local EV manufacturing base.

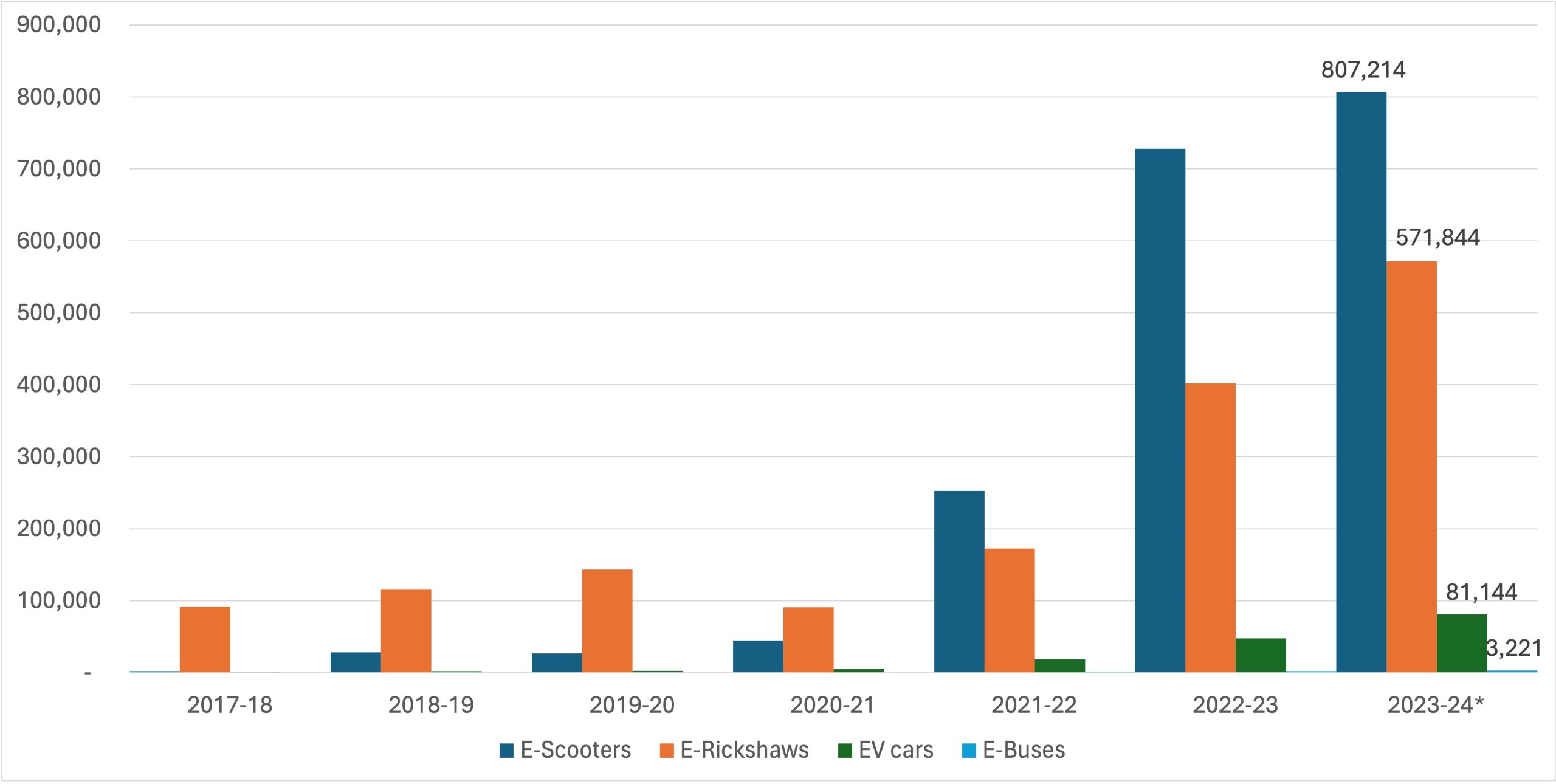

Figure 1 illustrates why this encouragement for local manufacture is needed. There has been massive growth in electric vehicles but little of it is in EV cars.

Figure 1: Annual sales of Indian electric vehicles

*2023-24 sales are till end February. All data from the Vahaan database

Electric versions comprise around 4% of total scooter sales, a staggering 50% of three-wheeler sales but only around 1% of car sales. Three wheelers, a peculiarly Indian vehicle class, provides last-mile commercial deliveries and short hop taxi rides. Its electric-vehicle’s home turf since 3-wheelers small batteries don’t need dedicated charging infrastructure and the higher capital costs are quickly defrayed by lower operating costs compared to the petrol-engine equivalent.

The growth in 2-wheel electric scooter sales, the stalwart of Indian personal mobility, is mind boggling – a twelve-fold growth in just 5 years. The largest manufacturer Ola Electric only came into existence in 2017. Two other large companies, Ather and Okinawa, are also less than 10-year-old. Traditional 2-wheeler manufacturers like Hero and Royal Enfield beloved by bike enthusiasts are stuck in first gear. India’s best-selling 2-wheeler is the Ola S1 Pro. It costs around Rs1.29 lakh (£1,300) and has a feature list that could have been copied from Tesla’s: an Ola app, proximity unlock, decent display with maps, and regenerative braking. It’s 4kWh battery takes 6.5hrs to fully charge using a 750W charger that can plug in any wall socket. Its energy efficiency is 25 Wh/km. The contrast with cars is significant the most efficient electric car retailing in the UK is the Peugot e-308 which manages 127 Wh/km, while the Tesla 3 achieves 150 Wh/km.

E-Scooters have taken off through subsides: namely the Faster Adoption and Manufacture of (hybrid and) Electric-vehicles policy. Its first version FAME-I ran between 2015 and 2019, FAME-II ran between 2019 and 2023. FAME I had a budget of Rs 359 cr (£35m) and subsidised the sale of to 280,000 vehicles. FAME II expanded the programme, with a Rs 10,000 cr budget earmarked to support the purchase of 1.5 million 2- and 3- wheel vehicles, 50,000 cars and 7,000 buses. Subsidies were paid at roughly Rs 10,000 per kWh battery ranging from around Rs 250,000 for EVs like the Tata Nexon to Rs 50,000 for scooters like the Ola Pro. The outturns to date are interesting. Subsidies were paid out to just 19,000 EV cars, 153,000 3-wheelers and 1.3 million e-scooters. The limited take-up for cars is not hard to understand. Who’s interested in buying a car when there is no charging infrastructure? In the February interim-budget, the finance minister hinted at the switch in tack away from consumer subsidies to strengthening the ecosystem by supporting manufacture and charging infrastructure.

This brings us back to where this article starts. But is the finance minister’s instinct for supporting electric car manufacture correct?

My Brompton with a Swytch electric enhancement

Given the lack of road space in cities and bottlenecks in the electricity generating and grid capacity, India should be careful about encouraging a switch to electric cars. Unfortunately, most of the locally manufactured EVs are pitching for the luxury end of the market developing electric versions of their premium ICE model like the Tata Nexon EV. Such cars, especially if the driver is using AC to keep cool don’t save much CO2. Indian power production emits around 800gCO2/kWh. Nexon EV claims an efficiency of 86Wh/km. But a real world test achieved a more credible 147 Wh/km, which translates into 117gCO2/km at India’s grid average carbon intensity. The Nexon petrol variant claims a fuel efficiency that translates into emissions of 133gCO2/km. The real-life EV using average Indian electricity saves a measly 12% of GHG emissions. Why not just buy a small hybrid? Only the MG has broken ranks and is releasing the tiny MG Comet with a 17.3 kWh battery and claimed efficiency of 74Wh/km. Priced at Rs 8 lakh it is much cheaper than other Indian EVs. India’s top car manufacturer Maruti, India’s largest car manufacturer, is yet to launch an EV car. Its first launch slated for December is going to be an SUV.

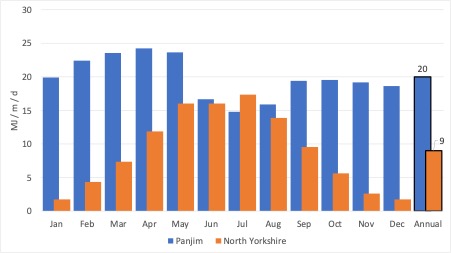

Cars are not the answer to personal transport in urban areas. E-Scooters are the best option for many journeys, but another priority should be to make cities walking and cycling. But if you are really interested in optimising performance nothing can beat my Swytch-enhanced Brompton. I bought a 250Wh battery pack during the lockdown and often go to the shops and back just 20% of my charge (though I pedal too). This equates to just 5 Wh/km and spares me climbing 160m from the escarpment where I live to the sea-level and back. A few cities are starting to adopt cycling. Over the last few months, I had the pleasure of biking in Chandigarh for three days, in central Bangalore for a pleasant afternoon, and for a terrifying hour in the cycling death-trap that is New Delhi. (I’ll cover public transport in another blog.)

Chandigarh not Amsterdam

So next budget, expected soon after the election results are announced in June, I hope the finance minister spend more on the less glamourous transport options including infrastructure for pedestrians and cyclists and maintains support for the e-scooters and rickshaws. The big unfinished business is heavy goods vehicles (40 and 50 tonnes) which ply India’s tiny urban roads and highways. These are responsible for 70 percent of vehicle air pollutants. Future blog.

The IMD’s record on long-range monsoon forecasting has been patchy. It failed to predict the droughts of 2002 and 2009, and in an evaluation conducted in 2019, RBI found no correlation between the IMD forecast of the volume and the actual rain.

The IMD’s record on long-range monsoon forecasting has been patchy. It failed to predict the droughts of 2002 and 2009, and in an evaluation conducted in 2019, RBI found no correlation between the IMD forecast of the volume and the actual rain.

RRR

RRR The

The  Who am I?

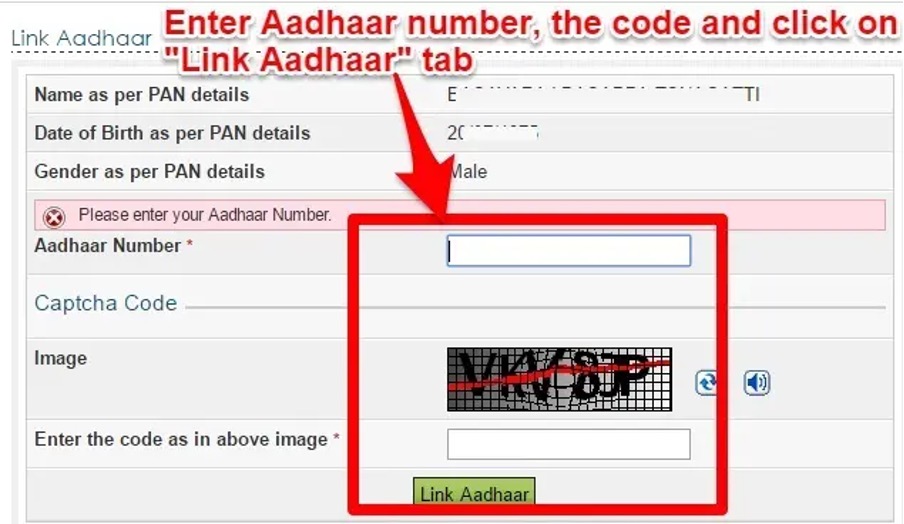

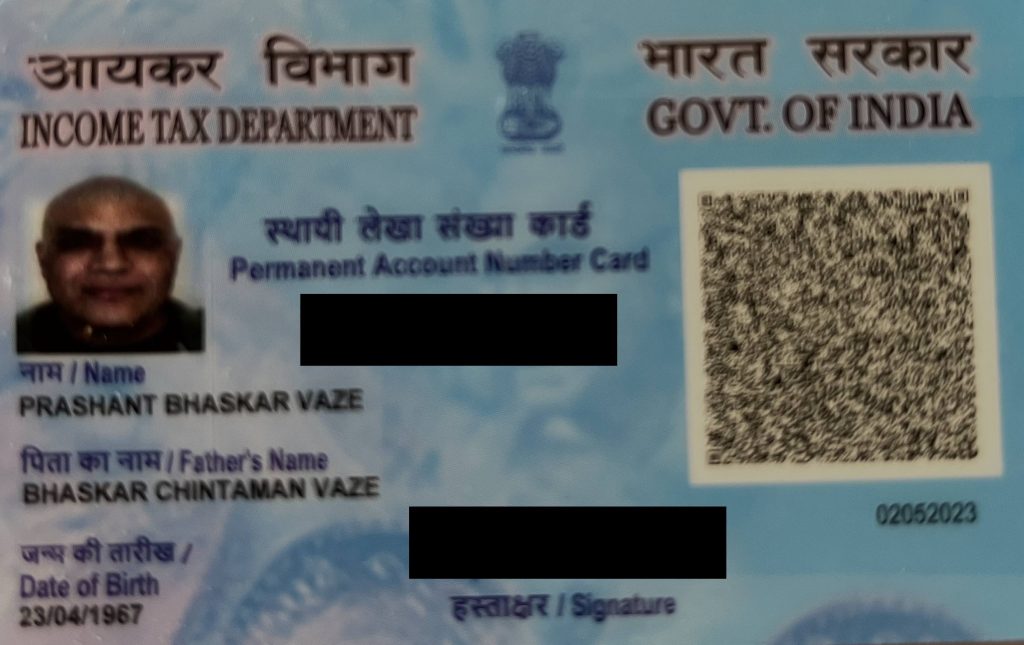

Who am I? The Permanent Account Number (PAN) is a ten-digit alphanumeric number, issued by two private companies – NSDL for online applicants, and UTI-TSL for paper-based applications – on behalf of the Income Tax Department. The UK equivalent is a National Insurance Number. (An interesting aside is that the code’s fourth character identifies the class of the applicant. ‘H’ signifies Hindu Undivided Family, and ‘J’ an Artificial Juridical Person, gratifying ChatGPT but leaving fractious, non-Hindu families beleaguered). You need a PAN to open a bank or savings account, purchase a car, insurance, jewellery, or property, apply for a phone number, and pay more than Rs 50,000 (£500) at a hotel or restaurant. The rationale for demanding PAN numbers is that India has a big problem with black money, and making buyers disclose PAN numbers cracks-down on crooks’ efforts to clean their loot.

The Permanent Account Number (PAN) is a ten-digit alphanumeric number, issued by two private companies – NSDL for online applicants, and UTI-TSL for paper-based applications – on behalf of the Income Tax Department. The UK equivalent is a National Insurance Number. (An interesting aside is that the code’s fourth character identifies the class of the applicant. ‘H’ signifies Hindu Undivided Family, and ‘J’ an Artificial Juridical Person, gratifying ChatGPT but leaving fractious, non-Hindu families beleaguered). You need a PAN to open a bank or savings account, purchase a car, insurance, jewellery, or property, apply for a phone number, and pay more than Rs 50,000 (£500) at a hotel or restaurant. The rationale for demanding PAN numbers is that India has a big problem with black money, and making buyers disclose PAN numbers cracks-down on crooks’ efforts to clean their loot. Getting an

Getting an