When we moved to Goa, one of my ambitions was to install solar PV at our flat. I have always been a bit iffy about the merits of solar in the UK because of its low overall yield and the fact output is pitiful in winter when the UK grid most needs power. But in India, it’s a no-brainer. The country has terrific solar resources. Even rainy, coastal Goa receives 9 or 10 hours of sun a day for eight months a year and even during the monsoon five or so hours of sun. Plus, the national government is supportive, with a crazy ambitious target of 500 GW of renewable energy by 2030. The lion’s share is likely to be solar some of it smallscale. Goa’s state government has promised to roll out a new solar and renewable energy policy with Goa Chief Minister Sawant recognising (a little late): “With it being the land of sun and sand, Goa provides the perfect setting to harness solar energy.”

The subsidy is notionally 50% of the capital costs of the panels, but politicians have fiddled with definition every year and the basis of comparison is set at the lowest discovered rate in the country of Rs 37,640/kW. This represents a subsidy of 22% of the installation costs I have been quoted. In exchange, I have to use an installer empanelled by the Ministry of New and Renewable Energy (MNRE) and buy Indian-manufactured panels.

Does the economics of domestic solar stack up? How easy will it be to get permission in our housing society with its Byzantine byelaws and sensitivities?

Our 14.5-metre square carport and oven of a car

We live in a first-floor flat, in a four-floor building. The roof belongs to our upstairs neighbours. We do have a dedicated 15 m2 car park space, where the asphalt gets hot enough to fry eggs, though the space is shaded in the afternoon. A solar canopy would help keep the car cool as well as provide power.

First, a primer of why solar makes sense in India. Goa gets over 1400 kWh of irradiation per square meter every year, two-thirds more than London. As the sun is slightly more vertical in the Indian sky an optimally angled 1 kW of solar panel gets 2000 kWh per year per panel compared to just 1180 kWh in the UK. Our enthusiastic installer is quoting Rs 280,000 (Rs 220,000 after subsidy) for a 3.24kW system. The panels are bifacial which means they can utilise light reflected off the car boosting yields by 30 percent offsetting the afternoon shading. We calculate the system will generate just over 12 kWh/d or 4.6 MWh annually. Over the day, generation follows a bell shape from six in the morning to six in the evening peaking at noon closely tracking demand from the fridge and AC units.

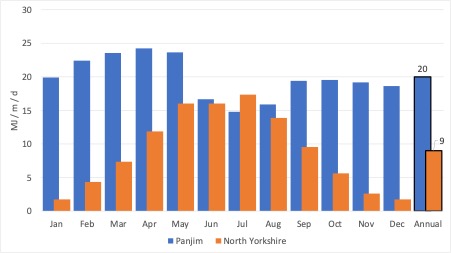

The generation over the year is also pretty steady compared to the UK’s peaking in the searing hot summer and dropping back during the cloudy monsoon period of June to August. UK in fact gets slightly more sunshine than Goa in July, but yields are pitiful in winter when the UK will really need power for heat pumps.

Daily energy of sunlight per metre square across the year central UK and Goa

We have only lived in Goa for a few months so no annual consumption data. Projecting from the bills so far, we look set for around 6.7 MWh. That’s barely a third of our combined electricity and gas use in the UK! I check my numbers to make sure there’s no mistake. I thought the air conditioning would cause a big upsurge in our electricity use. But it hasn’t. An AC is basically an air source heat pump plumbed backwards (rejecting heat outside and cooling the inside), an AC unit delivering 5 kW of cooling, adequate for our living room, draws only 1.5k W of electricity. Contrast this with the 18kW of gas used by our combi-boiler busy unnecessarily heating all the radiators in the house. In actual fact, we don’t use the air conditioning much, since the 75 W ceiling fan keeps us cool most of the time.

I forecast the solar panels will generate around two-thirds of our annual energy consumption all for the princely down payment of Rs 220,000 (around £2,200 which was roughly our energy annual energy bill in the UK).

It sounds like a no-brainer. It would be except, that electricity in Goa is unbelievably cheap, so our bill is just £240 a year, barely an eighth of the cost in the UK. In India, the state government owns the Distribution Companies (DISCOMs) which distribute and supply power. They hold household prices ruinously low running up losses, and often racking up unpaid debts to the merchant generators that feed into the grid. Goa operates a rising block tariff where the first units consumed in a month are much cheaper than later units further subsidising low-use households. Our first 120kWh of electricity per month is charged at just Rs 1.6 / kWh, a tenth of the tariff in the UK. Subsequent units are more expensive but the highest slab we pay is still only Rs 3.9 / kWh.

But the cheap electricity and low consumption means our solar panels will save us around two-thirds of our bill, barely Rs15,000 a year giving a payback of around 14 years.

I still want to do it, but you can see how policies to provide household customers cheap power impede the take-up of domestic rooftop solar. The flip side is that commercial customers who aren’t subsidised will find it much more profitable.

Anyway, we now have a quote, and we have the acquiescence of the other five owners in the building. But that’s only stage one of the process. I now have to contend with the non-existent housing society that runs the four hundred villas and flats in the estate, and the developer that manages the external facades of the building.

I will report back with an update in a few months. I have a hunch that doing the sums and getting a quote was the easy bit.