So my three and a half years in Hong Kong are up and I’m wending my way back to the UK tomorrow via the Silk Road over the next four weeks. In my work here, I often suggest environmental policies from other countries that Hong Kong might adopt. But knowledge transfer has traditionally wafted the other way, from East to West. So I thought I’d use my last Hong Kong blog to about what Hong Kong can teach policy makers in the West.

1. The MTR (Mass Transit Railway)

Now carrying around 5.79 million passengers a day in Hong Kong and another 6.49 million overseas (yes: it’s managing lines in China, London and Stockholm) almost half of the city’s public transport trips are undertaken on the MTR. It’s so much part of the everyday fabric, it’s hard to believe Hong Kong’s “underground” only commenced operations in 1979. It’s hugely profitable, even disregarding its property income, has a punctuality of 99.9%, clean and is incredibly easy to use.

What makes MTR unusual is the way it’s financed. Unlike other underground systems which struggle to secure capital budgets, MTR is awarded development rights for commercial and residential property around new MTR stations. So instead of the huge windfall rents from proximity to the MTR station being appropriated by those owning plots near the new station, the gains can go into investment into new lines. In the three years we’ve been here we’ve watched two lines being extended, and one entirely new line open up.

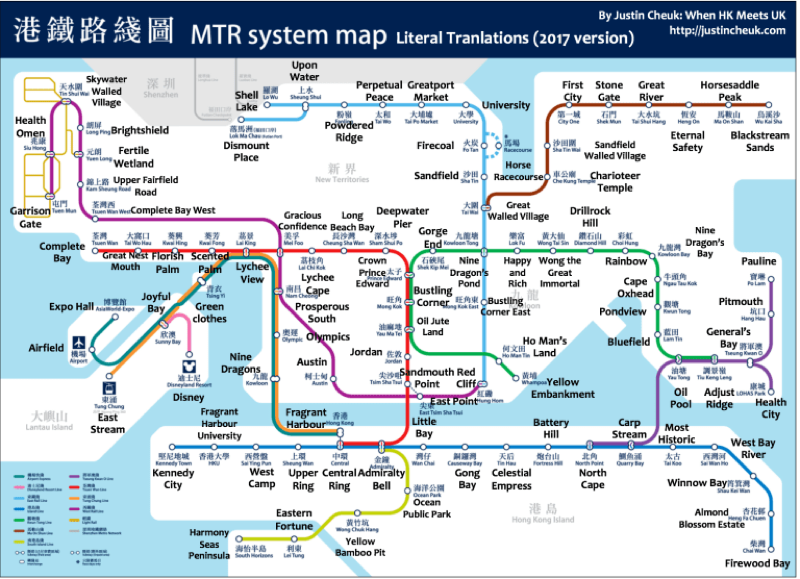

idiosyncratic map of the MTR

The contactless payment system devised by the MTR, the Octopus card, is Hong Kong’s de factolocal currency, and used for 14 million payment transactions a day. It’s widely accepted in shops and cafes, and is the only way to pay for parking meters. It’s so ubiquitous that the card’s magnetic strip is used as access control cards in many residential building complexes and schools. Pretty much all our visitors have picked one up at the airport and used it seamlessly for their travel and snack purchases over their stays.

Do understand MTR’s environmental success you just need to think about what transport and associated emissions would have been without it. The Hong Kong MTR’s electricity consumption was 1600 GWh last year – around 1 MtCO2, 2 per cent, of the cities total emssions. Unleaded petrol (used by taxis and private cars) in the city was responsible was 1.5 MtCO2emissions. This is despite only 14.4 percent of households having access to private cars and each private car only being driven 30 km/d on average. That’s right. Only one in six households in Hong Kong have a car. Most people, even well-off people, choose to use public transport and taxis. Think what transport emissions would be if the other five sixths of households without cars bought vehicles of their own.

As well as changing the pay we spend and travel, the MTR has changed where people live, stretching the widely habitated areas suitable for commuters off Hong Kong island, out of Kowloon through the 600-metre mountain ranges into areas of the New Territories like Shatin, Tai Po, Fan Ling, Tseung Kwan O, Yuen Long.

2. High density accommodation

The city makes use of all three spatial dimensions. Hong Kong’s 7.5 million people live in just 42,000 buildings; of these 8000 are high rise. Our current flat is in a 50-storey building; our previous in a 66-storey. Our ‘luxury’ estate comprises 17 towers set in 9 hectares of space and accommodating 20,000 people. The blocks are skirted by lawns, trees, play areas, indoor and outdoor swimming pools, tennis and squash courts, gym, soft play area, halls for hire, snooker facilities, a bowling alley and supermarket. By way of comparison, Highgate Camden in central London has an area of 320 hectares (150 hectares excluding the heath) and a population of 10,000 people.

This extreme high density means that the whole of Hong Kong’s population lives on just 70 km2of space with a density of 100,000 people per square kilometre, with the vast majority of people in the ultra-compact space around the MTR and bus stations. This means that the “last-mile’ journey either end of the MTR is usually not a mile, but a couple of hundred metres easily provisioned by tunnels and above ground walkways. At its extreme is the tangle of thru-building walkways permeating the Hongkong Land’s Central portfolio. Major MTR stations are embedded inside shopping malls and surrounded by residential or offices. The towering IFC and ICC blocks are built over the Hong Kong and Kowloon MTR stations.

Tangle of above ground public walkways weaving through shops, hotels, banks and offices in Central

This extreme concentration of habitation helps the environment not just by improving the economics and logistics of mass-transport systems but by freeing up land for nature.

There is a down side to the parsimonious way land is made available for urban uses. Developers and government conspire in driving up property prices so each flat is tiny and crowded to European sensibilities and inadequate for many Hong Kong people too. Hong Kong people’s homes are 15 square metres per person; half that in Singapore, or Tokyo.

3. Country Parks

Seventy-five percent of Hong Kong’s land territory is non-built up, over half of this, 444 km2, consists of country parks and other designated special areas. Unlike national parks in the UK no farming or forestry takes place. The space is slowly reverting back to forests, mangroves, coastlines and bare hill face. These parks and special sites are home to 2100 species of local plant, 50 species of mammal: from deer, porcupine, bats and macaques, 540 species of bird.

The country parks are criss-crossed by the MacLehose, Lantau, Wilson trails creating a wonderful and easily accessed corridor into nature used by 17 million people a year. It is hard to believe but nearly all the country park forests and grass lands are new growth re-established after the second world war. Well before the British came in the 1840s, Hong Kong’s mountains and uplands had been cleared of their trees to make charcoal and timber. Landslides and erosion had washed away the top-soil. Replanting began at the end of the 19thcentury, but the second world war denuded the landscape of its trees once more. The Country Parks Ordinance was enacted in 1976 to provide open space for recreation and to collect rainwater for the reservoirs. The different trails were laid in the late 1970s to link the country parks to one another.

Views from Lantau North Country Park, Lantau and Lung Fu Shan Country Park, Hong Kong Island

I am not aware of any other city that manages to squeeze so much nature so close to millions of people. But I hope the other mega-cities in the Greater Bay Area and elsewhere in Asia try and emulate. As well as improving local air quality, it provides fantastic recreation right on the door step.

4. Banning of trawling

Go to any wet market and you can see Hong Kong people love eating fish: croakers, groupers, bream.

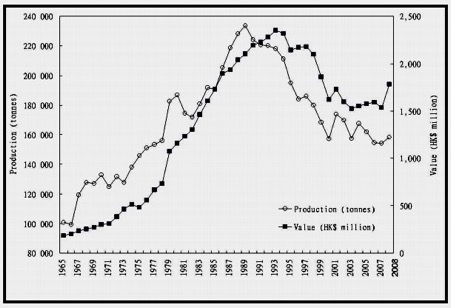

Volume and value of the Hong Kong fishing fleet 1965-2008, LegCo

It’s hard to believe but until the 1970s fishing was still carried out off sailing junks using traditional lines. But Government programmes encouraging investment and better integration if the Hakka fishers, saw the fleets ‘modernisation’ replacing wind-power with diesel; lines with trawlers. The predictable result echoed that seen in fisheries world over. The diagram above shows the swift boom and bust cycle of rapid expansion in catch until 1989, followed by an equally rapid decline. In the battle between nature and technological mining of nature there is only ever one winner. The cod and haddock fisheries in the North Sea and the Grand Banks of USA/Canada similarly collapsed.

But then Hong Kong did something different, the government courageously banned trawling at the start of 2013. Trawling, the raking of the seabed to indiscriminately snare everything on the sea bed regardless of whether it’s edible, used to account for 80 percent of fishers’ incomes when the ban came in. By the end of 2015, government paid 1250 vessel owners almost $1 billion in one-off buy outs. Money has been loaned to retrain fishers, or to finance the switch to aquaculture/mariculture and fisheries related eco-tourism. There is also extensive co-operation between Hong Kong and the Guangdong Fisheries Administration General Brigade to ensure illegal .

The first-year results are encouraging with a 50 percent increase in the catch of bottom dwelling species, and a doubling in the waters where trawling used to be most intense. But it’ll take years for the communities on the sea-bed to recover and other measures like proper stock assessments over the South China Sea and the establishment of marine nature reserves are needed to make a real in-road.

There were other things that could have been included on the list but didn’t quite make the cut. The mandatory switching to low-sulphur fuel while vessels are berthed was an excellent bit of legislation to improve air quality, but is rapidly being superseded by more stringent regulations from Beijing covering all Chinese waters. I was tempted to write about the excellent network of cycle lanes spreading through the New territories and the dockless bike hire companies like Hong Kong’s Gobee (which sadly is closing due to competition from superior, and better financed, Chinese competitors like Ofo). With cycling Hong Kong is playing catch-up with Guangdong.

Another initiative that didn’t quite make the mark was the recent push by the government to position HK as a green finance hub including support for issuing green bonds in Hong Kong and using the HK Quality Assurance Agency to certify green bonds.

Perhaps these three near successes are part of the bigger story. The real hub of environmental leadership is taking place north of the Shenzhen River in mainland China.